-

San Diego sheriff: Migrants did not try to forcefully stop school bus - August 31, 2024

-

One stabbed, another injured in altercation on L.A. Metro bus - August 31, 2024

-

Trump Judge Has ‘Two Options’ as Future of Case Unclear: Analyst - August 31, 2024

-

What to Know About Putin’s Planned Visit to Mongolia Amid ICC Arrest Warrant - August 31, 2024

-

Buying sex from a minor could be a felony under bill headed to Newsom - August 31, 2024

-

Democrat Lawmaker Switches Party to Become Republican - August 31, 2024

-

Misdated Mail-In Ballots Should Still Count, Pennsylvania Court Rules - August 31, 2024

-

Cause and manner of death determined for Lucy-Bleu Knight - August 31, 2024

-

NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series Announces Return To Iconic Circuit In 2025 - August 31, 2024

-

At Pennsylvania Rally, Trump Tries to Explain Arlington Cemetery Clash - August 31, 2024

How much worse will extreme heat get in U.S. by 2050?

The next quarter of a century will bring considerable climate danger to millions of Americans living in disadvantaged communities, who will not only experience increased exposure to life-threatening extreme heat but also greater hardships from reduced energy reliability, a new nationwide report has found.

The report, published Wednesday by the ICF Climate Center, examines global warming projections in Justice40 communities — those identified by the federal government as marginalized, underserved and overburdened by pollution. The Justice40 Initiative was established under President Biden’s strategy to tackle the climate crisis, which aims to funnel 40% of benefits from certain federal climate, energy and housing investments into these communities.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

But the report outlines a stark future for residents in these areas, including many in California.

Under a moderate-emissions scenario — one in which current fossil fuel consumption peaks in the coming decades and then starts to decline — at least 25 million people in disadvantaged communities will be exposed to health-threatening extreme heat annually by 2050, the report found.

Under a high-emissions scenario, reflecting unchanged “business as usual” greenhouse gas emissions, that number soars to 53 million people. Extreme heat is defined as at least 48 health-threatening heat days per year.

“We were a bit surprised at those numbers — they’re large and meaningful,” said Mason Fried, one of the report’s authors and the director of climate science at ICF, a global consulting firm. “The potential exposure of extreme heat does seem to fall disproportionately on disadvantaged communities.”

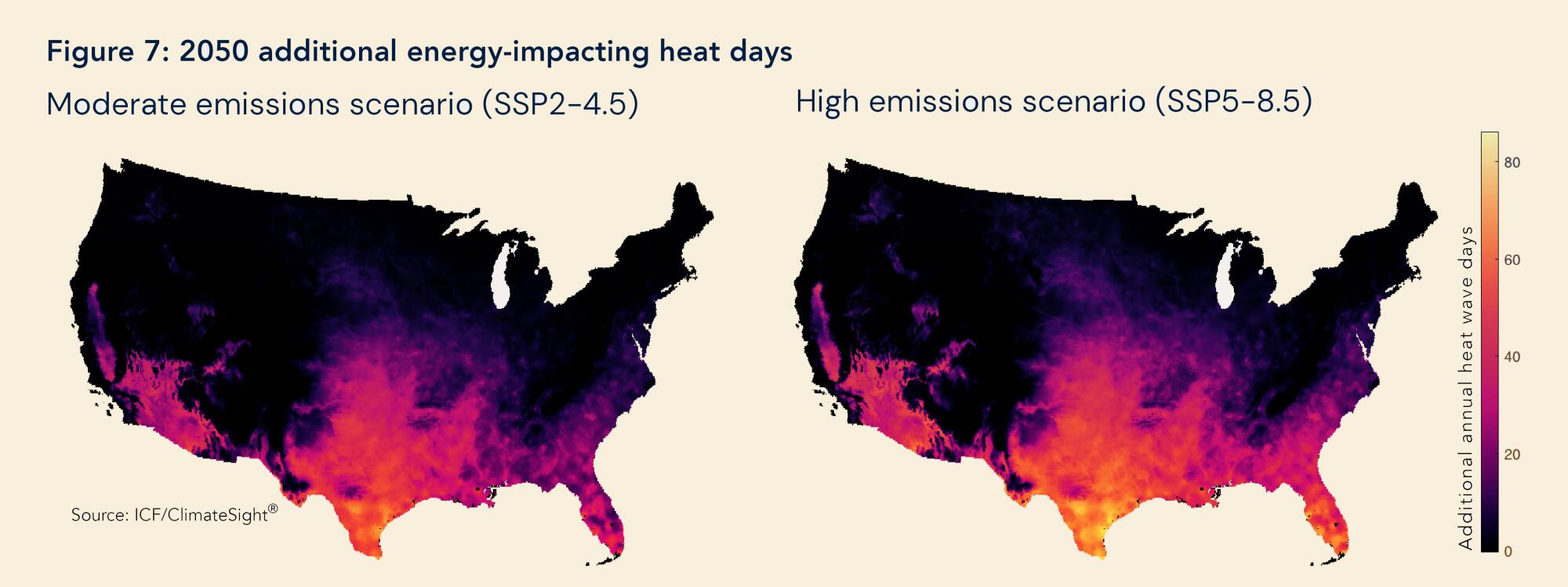

The report also notes that about 8 million people in Justice40 communities are already exposed to heat waves that can affect their energy systems, including triggering power outages. But by 2050, that number could rise to 34 million under a moderate-emissions scenario and 43 million under a high-emissions scenario.

It isn’t only disadvantaged communities that will experience the worsening effects of extreme heat, which is one of the deadliest and most widespread climate risks.

Under a moderate-emissions scenario — the most likely one — 41 million Americans outside of Justice40 communities will also be exposed to 48 or more health-threatening heat days by 2050, and 44 million will experience energy-impacting heat, the report found.

The effects will not be equal, however. Many marginalized communities are already at a disadvantage when it comes to extreme heat for a variety of reasons, including the population’s average age and preexisting health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, which can be exacerbated by heat.

Lack of tree canopy, lack of air conditioning at home or work and inefficient infrastructure can also play a part, said V. Kelly Turner, an associate director of urban planning at UCLA who did not work on the report.

“Everybody’s going to be exposed to more heat, so is the question really, how much more exposed? Or is the question, how many people are living with inadequate infrastructure to keep them safe when it is hot?” said Turner, who also co-directs the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

In places like Los Angeles, temperatures can vary by several degrees between neighboring areas just because of differences in vegetation, asphalt and the built environment.

Even still, many Angelenos are better acclimated to higher temperatures than people in cooler parts of the state or country, Turner said.

“It’s about what you’re used to versus what you’re exposed to,” she said.

That’s why the report’s findings about energy impacts are particularly worrisome.

“It’s those northern latitude communities where this might become particularly difficult if the energy grid fails,” she said. “In Northern California [and places] where you aren’t thinking about heat all the time, that’s where maybe you’re not prepared as much.”

Indeed, the report’s projections show an intensification of potential exposure not only in traditionally hot areas, but in regions that historically have not experienced very high temperatures, such as the Northwest and Midwest. Fried referenced the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome, which caused more than 650 deaths in the U.S. and Canada.

“It’s a phase change,” he said. “It’s a fundamentally different kind of exposure, which could have outsize impacts in the future.”

In fact, the report shows, most of California will in some ways fare better than other parts of the country, such as Texas and the Southeast, which are expected to see some of the worst heat outcomes by 2050.

Only a smattering of Justice40 communities in the Golden State will see 48 or more health-threatening heat days under a moderate-emissions scenario, with additional communities appearing under a high-emissions scenario.

But the Central Valley and southeastern California light up like a summer fireworks show when it comes to energy-impacting heat days, the report shows — meaning many people in those areas could suffer from power outages and swelter without air conditioning or other forms of relief.

“It doesn’t take much, or a large increase in extreme heat, to get a tipping point there,” Fried said.

Increasing heat days could affect energy systems across the country by 2050, including in California. Projections are worse under a high-emissions scenario.

(ICF / ClimateSight)

The report outlines a number of high-level recommendations for policymakers, such as identifying at-risk communities and engaging stakeholders in the planning and preparation for these scenarios. It also points out that more federal funding is being made available to tackle extreme heat through Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Among those federal endeavors are two new national centers to support community heat monitoring and resilience, which were announced this week by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

One federal center will be based in Durham, N.C., and the other will be at UCLA and directed by Turner, who described it as “an all-hands-on-deck approach to learn from existing efforts to prevent the worst consequences of extreme heat.”

The center will work to get nonprofit organizations, cities, academic institutions and international and tribal communities into the same room to distill general and specific lessons and help determine the best paths forward, Turner said. It will also fund 10 communities over each of the next three years with the goal of providing recommendations to the federal government about how best to “support local communities as they transition to a more heat-resilient future.”

Turner said California and Los Angeles are doing a good job, but should look beyond efforts such as urban tree canopy improvements and cool roof and pavement installations. There is more to do, including deeper analysis of heat exposure in specific locales and regulations that can have an effect.

Her recommendations include rethinking how the Federal Emergency Management System evaluates heat risk and property damage; ensuring that vulnerable communities have the technical support they need to apply for grants and secure funding; creating low-income housing energy assistance programs; and passing legislation to provide cooling to all residents, Turner said.

She pointed to California’s plan to establish the first statewide ranking system for heat waves as a positive example, as well as new heat monitoring tools from NOAA and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The ICF report comes at a moment when heat records are continually being broken around the globe, with 2023 going down as the planet’s hottest year on record.

What’s more, the 2050 projections are for a “typical year,” but Fried said recent experience has shown many years can be atypical due to El Niño or other effects that can make them far warmer, with even worse potential outcomes.

That’s why it’s not only important to help vulnerable populations prepare for a warmer future, but also to continue pushing to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and other sources of planet-warming emissions that are driving the scenarios depicted in the report, he said.

“If we take steps to mitigate emissions, we can do better than what’s pictured here,” he said.

Source link