-

San Diego sheriff: Migrants did not try to forcefully stop school bus - August 31, 2024

-

One stabbed, another injured in altercation on L.A. Metro bus - August 31, 2024

-

Trump Judge Has ‘Two Options’ as Future of Case Unclear: Analyst - August 31, 2024

-

What to Know About Putin’s Planned Visit to Mongolia Amid ICC Arrest Warrant - August 31, 2024

-

Buying sex from a minor could be a felony under bill headed to Newsom - August 31, 2024

-

Democrat Lawmaker Switches Party to Become Republican - August 31, 2024

-

Misdated Mail-In Ballots Should Still Count, Pennsylvania Court Rules - August 31, 2024

-

Cause and manner of death determined for Lucy-Bleu Knight - August 31, 2024

-

NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series Announces Return To Iconic Circuit In 2025 - August 31, 2024

-

At Pennsylvania Rally, Trump Tries to Explain Arlington Cemetery Clash - August 31, 2024

Homeless L.A. public school students honored at a special graduation ceremony

One student lived variously in a car, a homeless shelter, motels and with relatives. Another was kicked out of the house in high school. And yet another shared one room with his entire family and worked washing dishes.

These Los Angeles Unified high school students represent a complex mosaic of hardship, but also have overcome tremendous adversity — and were among 130 who were honored Monday by the district at BMO Stadium south of downtown, where many received college scholarships.

“You’re here because you accomplished something, because you made sure your life has meaning,” author Luis Rodriguez said in remarks to the graduates.

Rodriguez, who also overcame hardship in his youth, told the graduates to learn to love themselves in a positive way and “the angels will come out of the woodwork — the teachers and the mentors and the people will come out to help you. That’s been my experience.”

About 15,000 students experience homelessness in the L.A. Unified School District, an increase of about 3,000 students or about 25% from the previous year. These numbers are “likely an undercount — as students self-identify as experiencing homelessness,” said district spokesman Britt A. Vaughan. Across L.A. County, about 47,700 students faced housing instability during the 2022-23 school year — out of nearly 1.4 million students.

In a given year, about 11% of California students experiencing homelessness will spend time either living in a temporary shelter or under no roof at all. An additional 6% will be living in a hotel.

School is her stability

Janai Johnson from James Monroe High School was a featured speaker at a recognition ceremony honoring graduating students who, like her, had overcome homelessness.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

Janai Johnson said she was determined to achieve stability once she walked through the schoolhouse door at Monroe High in the San Fernando Valley. She was going to stay in school — and stay in that particular school. Her mother shared that determination, although the breakup with her husband — a necessity, says Janai — made things harder financially.

“I’ve been in and out of homeless shelters, motels, and we’ve bounced around with different family members across California,” Janai said. “So that definitely does take a toll.”

Janai’s mom found shelter and work at the downtown Union Rescue Mission, but it was more than 23 miles away from Monroe High — more than an hour’s drive during peak traffic. Still, that was a breeze compared with more than a year they spent in a small apartment in Moreno Valley, when her mother drove her 85 miles and two hours each way.

“Me and my mom are extremely close,” Janai said. “She’s been my No. 1 supporter forever. She constantly tells me how proud she is and that, if I get a higher education, things will be easier for me. And I think that’s why I’ve always been so interested in college.”

Janai remembers having to get to school early — being the first to arrive and shivering in the morning chill. She fought to be active in school activities. These included a program called AVID, which helps prepare students for college and careers. Her mom never got to finish college.

Sometimes the schedule was too much and Janai would fall asleep in class — but her teachers were understanding. And she’s managed to maintain a 3.0 GPA.

Janai plans to study early childhood development at Cal State Channel Islands.

On his own

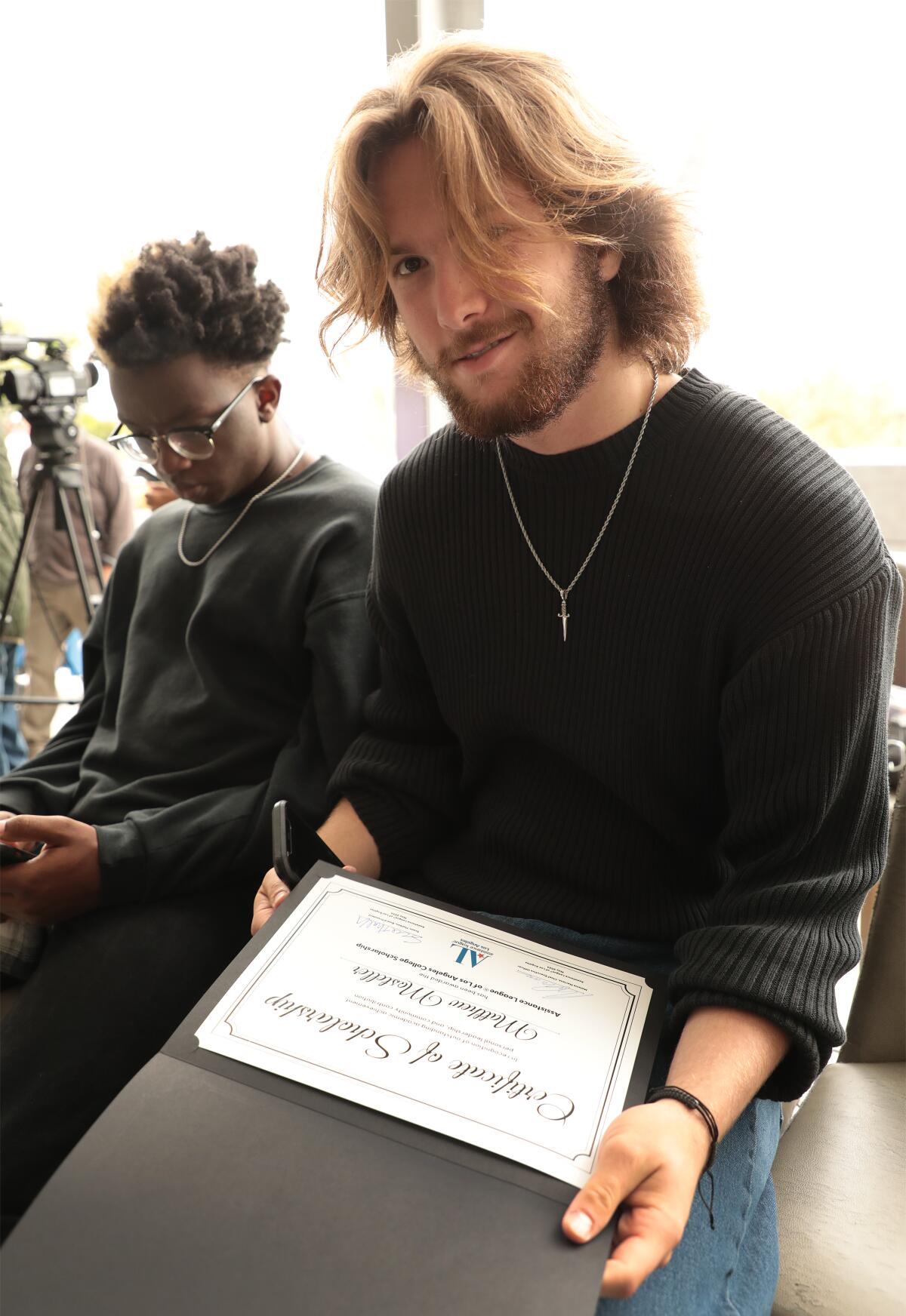

Matthew Mosteller from Grant High looks at his scholarship certificate after the end of the ceremony. About 130 seniors participated.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

The state defines homeless youths as those who “lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.”

Matthew Mosteller’s mother died in childbirth. His grieving father wasn’t prepared to raise a child, so Matthew’s grandparents stepped in, he said. When his father returned to the picture, Matthew lived with him. But Matthew said he was rebellious — and his father entered a new relationship — followed by a baby. Matthew got kicked out at 17 and had to make it on his own, working at a pizza restaurant, he said. That’s not enough to pay for his own place, so he has moved around.

But he didn’t give up on having a life at school. He won election as a student body officer and became a peer counselor — while maintaining a 3.97 GPA. Matthew plans to be a firefighter, most likely going to a local community college to earn the necessary credentials.

“I was stressed because of how difficult it would be,” Matthew said. “But at the end of the day, I knew I would still be able to succeed and rise above everything.”

College-bound

According to census data, approximately 15,307 California students experiencing homelessness were enrolled in the 12th grade during the 2022-23 academic year. Only about half enroll in college, even though data indicate that an overwhelming majority wish to pursue careers that require post-high school education. A bill by state Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San José) could help — by providing several months of modest guaranteed income that would bridge the time between high school graduation and the start of college.

Housing instability takes many forms, including living in overcrowded, substandard situations. Juan Mesa has been living with his parents and younger brother in a single room in an apartment without air conditioning they share with another family.

About 8 in 10 students experiencing unstable housing share small spaces with more than one family, according to state data.

Juan Mesa from Edward R. Roybal Learning Center excelled in school despite having to work as a dishwasher and living in a one-room space with his parents and brother in an apartment shared with another family.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

When Juan was 15, his family emigrated from Bogota, Colombia — where his father was a teacher and his mother took on odd jobs. His father dreamed of a better opportunity for his children in the U.S. and spent several years saving up.

But poverty awaited them in Los Angeles, especially because it took a while before his parents were allowed to work. Juan helped out by working as a dishwasher 20 to 30 hours a week.

“We always had this belief of helping family — that’s something really important. So in tough moments, I step in and I had to get a job,” he said.

He excelled at Roybal Learning Center on the edge of downtown, speaking strong English within a year. He quickly moved into Advanced Placement English classes. He plans to major in the public health field when he begins at UC Davis in the fall.

Thriving in L.A.

Like many other unhoused students, Xavier Moreland moved from relative to relative at various times — and had to do so by himself, without a permanent attachment to a supportive family member.

“I was never, ever celebrated in my life for anything,” he said. “And it just sort of made me struggle in school. It was very hard for me socially, to get along with anyone else because that’s all I knew. And I was often bullied.”

Xavier grew up in Ohio, but was finally able to connect with a supportive older brother in L.A. His brother, other adults and friends helped him thrive and reach this graduation day, he said.

Xavier plans to attend community college in Napa Valley, where he hopes to learn about the hospitality industry.

Xavier Moreland from Grant High School said his life recently turned around after years of family instability.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

Source link